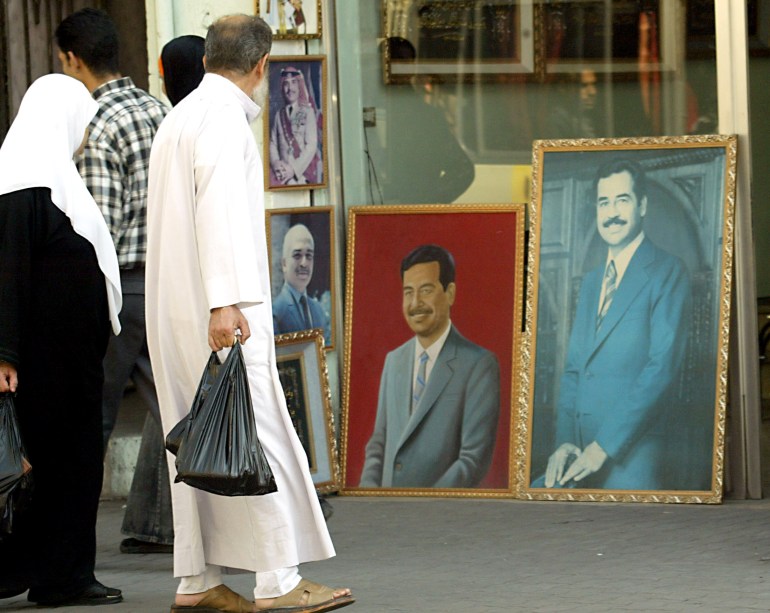

In the eyes of many Arabs, Saddam Hussein, the former dictator of Iraq, was a true leader who stood up to Western imperialism, the Israeli occupation of Palestine and foreign intervention in the region.

But to most Iraqis, Saddam was a tyrant whose 25-year reign from 1979 to 2003 was marked by brutal authoritarianism, repression and injustice, especially among the country’s Shiite and Kurdish communities.

Twenty years after the 2003 United States-led invasion of Iraq, which, in the words of former US President George W. Bush, aimed to “liberate the Iraqi people” from the oppression of their ruler, Saddam’s memory remains divisive and polarizing. But for many, the economic and political chaos unleashed by the invasion was more than ever a lion of Saddam and his legacy.

“Saddam embodied the image of the strongman who rose up against the US, Israel and Iran – all the traditional ‘bad guys’ in the [regional] story,” says Fanar Haddad, an expert on Iraq and assistant professor at the University of Copenhagen.

“This story deepened after the 2003 invasion as a way of opposing the occupation and order that emerged. The fetishization of Saddam was a resistance to what was happening,” he told Al Jazeera.

The Palestinian case

Before Saddam came to power in 1979, the Baathist regime was part of the espoused anti-imperialist and anti-colonialist rhetoric, called for the unification of Arab countries and nationalized Iraqi oil by transferring foreign stocks in the early 1970s. to take.

It also swung the foreign policy of a regional power as it sought to diversify Iraq’s economy and develop its education system, infrastructure and social services.

In 1969, the Iraqi-led Baath Party founded the Arab Liberation Front, a small Palestinian political party that came under Saddam’s leadership and joined the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). The party supported a pan-Arab ideology that believed the Israeli-Palestinian conflict was not a specifically Palestinian issue, but rather an Arab issue for which Iraq must fight.

When Saddam became president, it came as no surprise that many Arabs supported the persona he portrayed as their defender and, above all, champion of the Palestinian cause.

In the early hours of January 18, 1991, Saddam launched several Scud missiles at Israel—a defining moment for Saddam’s image. The Iraqi strikes, three of which landed in Tel Aviv, came a day after Bush unleashed an attack on Baghdad over its invasion of Kuwait.

“Saddam stood up for us when no Arab leader did,” said Manal Mustafa of Jerusalem, referring to the attacks. The 72-year-old said she would always remember him for that.

Saddam also sheltered thousands of Palestinians in Iraq and gave them equal rights as Iraqi citizens at a time when Palestinian refugees in other Arab countries lived in derelict refugee camps and had limited access to employment, health care and education. With special status, Palestinians in Saddam’s Iraq were eligible for state jobs, free education and state housing.

Growing up in the 1980s and 1990s, Tunisian journalist Hadhami Khraief saw Saddam’s strong speeches in defense of Palestinian and Arab rights as an “outlet” for her generation’s frustrations over what she described as the impotence of Arab leaders against Western interventions.

“We weren’t concerned about how he was running Iraq,” Khraief said. “We were united by the common cause of Palestine. When Saddam declared that his country fully supported the Palestinians, we considered him a voice for us,” she added.

Arab ‘strong man’ and Gulf wars

According to independent political analyst Mamoon Alabbasi, the first Gulf War between Iraq and Iran further boosted Saddam’s regional popularity, making him stand out for “fighting foreign intervention” by Iran, while other Arab leaders were seen as “stooges installed by Western powers “. .

But unlike the Iran-Iraq war, in which many Arabs supported Saddam for deterring what they saw as an external threat, the Arabs did not support Saddam’s invasion of Kuwait, a fellow Arab state, in 1990.

“Without his disastrous decision to invade Kuwait, Saddam Hussein would have remained a national hero in the eyes of most Arabs,” retired Iraqi Brigadier General Sobhi Tawfiq told Al Jazeera. “And Iraq would have been spared the devastation and poverty that resulted from the inhumane [UN] sanctions and blockades.”

A UN-imposed embargo on Iraq in response to Baghdad’s invasion of Kuwait left Iraqis starving and unable to access medicines and other basic necessities. But while the Iraqis suffered under the siege, Saddam’s refusal to retreat glorified him in the eyes of the Arabs.

In addition, the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, the 2006 execution of Saddam on the day of Eid al-Adha, the country’s subsequent multi-layered decline and outbreaks of sectarian violence, political instability and rampant corruption among the US occupation many injustices committed by the Iraqi dictator from Arab memory.

“Contrary to what his opponents sought, the invasion of Iraq was a turning point that kept Saddam’s legacy alive. It revealed how much he had resisted the arrogance of the West,” Khraief said. “The day of his execution left us in great pain,” she added.

US claims of Iraqi weapons of mass destruction to justify the war against Baghdad were disqualified, but the invasion left a trail of destruction in the region that eventually led to the ISIL (ISIS) armed group.

Iraqi hatred mixed with nostalgia

While many Arabs supported Saddam before and after the US-led invasion of Iraq, most Iraqis continued to despise him for his ruthless authoritarianism that isolated Iraqi society.

“Most Iraqis still see him as a dictator and tyrant who destroyed and impoverished Iraq, squandered its economic potential and human resources and caused it to decline for decades,” said Iraqi writer Saman Nouh.

Farris Harram, an Iraqi academic and former president of the Writers’ Union in Najaf, told Al Jazeera that although Saddam had a sectarian approach and “repressed Shiites and Kurds in a concentrated manner, he was criminal and unjust to all”.

Alabbasi agreed: “Before the invasion, most Iraqis feared Saddam. It didn’t matter if they were Arab or Kurd, Sunni or Shiite, you hated him.”

Saddam’s most famous atrocities against his people included killing thousands of Kurds and Shiites as he suppressed insurgencies in the north and south in the 1990s.

The Anfal military offensive in the 1980s destroyed hundreds of villages and killed at least 100,000 Kurds, mostly civilians, leaving 180,000 dead by some estimates. During that campaign, Saddam ordered a chemical attack on the Kurdish village of Halabja on March 16, 1988, killing 5,000 people, mostly women and children.

In 1982, Saddam allegedly ordered the killing of 148 people in the Shiite village of Dujail over an assassination attempt on him while visiting.

He was later tried by an Iraqi court and hanged for the Dujail murders, after which the charges against him in the Anfal trial were dropped and the trial continued without him.

While many Iraqis supported their country during the first Gulf War, the implications of the eight-year war came at a huge human and economic cost, leading many to question whether it was justified.

“Many Iraqis believed that Saddam Hussein was the one who started the war with Iran,” said Tawfiq, who rose to the rank of brigadier general in the Iraqi army during the first Gulf War before retiring in 1988.

“The loss of tens of thousands of young Iraqis [during the war] and the wounding of many more, was a reason for many Iraqis to hate Saddam,” Tawfiq explains.

For US-based Iraqi journalist Riyadh Mohammed, Saddam was not only responsible for the outbreak of war with Iran, but he was also the cause of “all Iraq’s suffering”. He sent thousands of Iraqi men to their deaths, created an atmosphere of fear and poverty and sowed the first seeds of sectarianism, Mohammed said.

“That is why Arabs’ love for Saddam offends us. She [Arabs] I don’t know what Saddam has done to us,” Mohammed explained, adding that he was “very happy” that Saddam’s statue was toppled in Baghdad’s Firdos Square on April 9, 2003, a move that made headlines worldwide and became a symbol of the Western victory in Iraq.

But 20 years after that day, many Iraqis now feel nostalgic “for a time when Iraq was strong and respected,” Tawfiq said.

“Iraq under Saddam had global influence, developed economy, strong dinar [local currency], welfare, housing, health, education, bridges, roads, dams, airports, self-sufficiency and a respected passport,” said Tawfiq. “Iraqis remember that and want to go back.”

Harram agreed: “Some Iraqis now view Saddam as having retained the sovereignty of the state. They say his corruption and abuses were less compared to what we suffered under the post-2003 regime.